Every financial product, from a retail banking app to a global payment platform, relies on one invisible constant: the general ledger. The general ledger (GL) is the definitive record of all financial transactions – the mechanism that guarantees accounting accuracy and the foundation on which compliance, transparency, and trust are built.

In modern banking and Payment Service Providers (PSPs), a robust general ledger is more essential than ever. Institutions process enormous volumes of transactions (over 3.4 trillion payments globally in 2023 alone ), and without a resilient, real-time ledger at the core, no organisation can ensure operational integrity or scale effectively.

In this article:

- We explore what a general ledger is and why it’s critical in financial systems.

- We examine the structure of a GL – from accounts and journals to the double-entry principles that keep everything balanced.

- We look at real-world examples of how banks and PSPs use ledgers daily, and compare traditional ledgers with modern real-time accounting models.

- We also explain reconciliation: what it means, why it’s necessary, and how it’s done – including common use cases and industry tools.

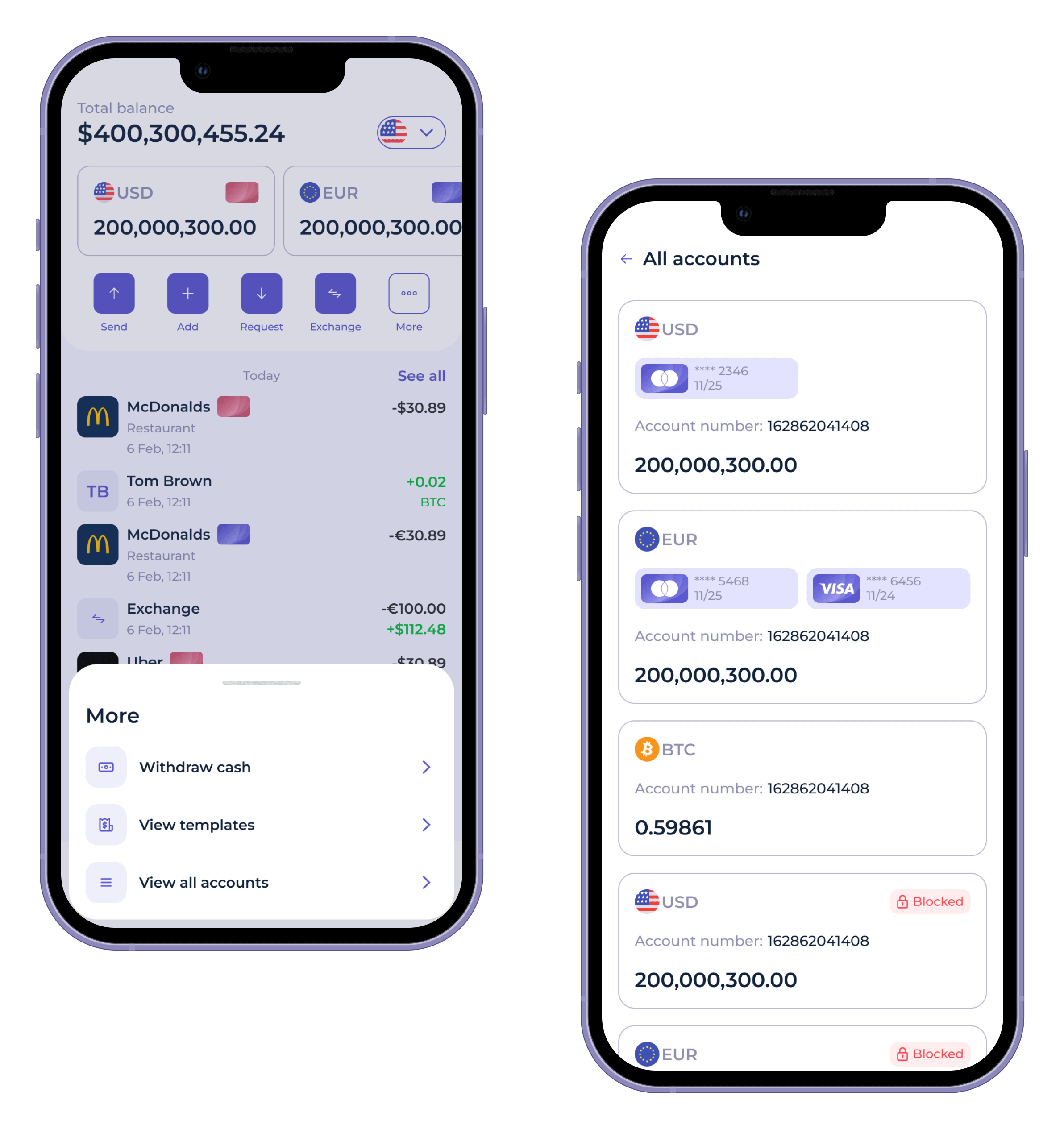

- Finally, we provide a case study of SDK.finance’s ledger-based platform, highlighting its real-time transaction processing, modular architecture, and built-in reconciliation tools.

What Is a General Ledger?

A general ledger is a core accounting record that serves as the central repository for all financial transactions of an organisation . It is a complete, chronological record of every debit and credit across all accounts - assets, liabilities, equity, revenue, and expenses - providing a comprehensive view of the company's financial activities.

The general ledger is vital because it consolidates financial data from all sub-ledgers and sources into one master record. This enables the preparation of accurate financial statements and regulatory reports. It acts as the “single source of truth” for an institution’s finances, which auditors and regulators rely on for verification .

Why is the general ledger especially essential in banking and payments?

In these industries, huge transaction volumes and strict oversight go hand-in-hand. The general ledger allows financial institutions to track every deposit, withdrawal, payment, fee, and interest accrual in real time and prove that customer balances and institutional accounts are correct at any moment. For example, regulators require that an electronic money institution’s internal ledger balances match its bank account balances precisely at all times – a task only feasible with a robust ledger system. Moreover, the general ledger underpins customer trust: when a PSP shows a merchant their available balance or a bank shows a customer their account balance, that figure ultimately comes from the general ledger’s accurate tally of transactions.

According to SDK.finance, a leading banking software provider, “moving from batch-based accounting to real-time ledger systems is no longer optional – it is a prerequisite for financial institutions that want to compete in digital-first markets.”

In summary, the general ledger is the cornerstone of financial systems. It provides real-time visibility into financial health, supports strategic decisions with historical data, and prevents small issues from snowballing by catching inconsistencies early through reconciliation. Whether it’s a global bank ensuring capital adequacy or a fintech app tracking e-wallet balances, the general ledger’s role as the central financial record is indispensable.

How Are Transactions Recorded in the General Ledger?

Transactions are recorded in the general ledger through a double-entry system that ensures accuracy and balance.

To build a general ledger using the double-entry bookkeeping method, every transaction must be recorded in at least two accounts, with one debit and one credit entry. The following steps outline the process:

1. Data collection

Organisations begin by gathering source documents such as bank and card statements, point-of-sale records, invoices, and receipts. These documents provide the raw data for ledger entries.

2. Journal entry

Each financial event is first recorded in a journal. Entries capture both debit and credit sides of the transaction, including the date, affected accounts, amounts, and a short description. Journals serve as the chronological log of all activity.

3. Classification

Transactions are then grouped into categories such as assets, liabilities, equity, revenue, and expenses. This classification ensures data is organised and easy to analyse.

4. Posting

Journal entries are transferred, or posted, to the appropriate general ledger accounts. Each posting includes an account number, date, amount, and description. Posting consolidates detailed entries into account-level summaries, keeping balances up to date.

5. Trial balance

A trial balance lists all ledger accounts and their debit or credit balances at a given time. Its purpose is to confirm that debits equal credits. Any imbalance signals potential errors in journalising or posting, requiring review and correction.

5. Account reconciliation

Reconciliation compares ledger balances with external records such as bank statements or loan statements. It helps identify missing items, value mismatches, or misclassified entries. Discrepancies must be analysed and resolved to ensure accuracy.

6. Adjusting journal entries

Adjusting entries record temporary changes like accrued expenses or correct errors uncovered during reconciliation. They ensure the general ledger reflects the organisation’s actual financial position. Every adjustment should be well documented and supported by evidence.

7. Financial statements and reports

Once all entries are posted and adjusted, the general ledger becomes the foundation for preparing financial statements – the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement – providing a complete and compliant view of the organisation’s performance.

This simple mechanism scales to millions of transactions in banks and PSPs. Each payment, fee, or adjustment becomes a set of balanced entries in the general ledger, creating a complete audit trail of financial activity.

Structure of a General Ledger: Accounts, Journals, and Double-Entry

The GL is structured to systematically record and summarise every financial transaction. Key components include:

- Accounts and Chart of Accounts (CoA) – categories such as Cash, Accounts Receivable, Accounts Payable, Revenue, and Expenses.

- Journals and Posting – where transactions are first recorded before being posted to accounts.

- Double-Entry Bookkeeping – every transaction has equal debits and credits, ensuring balance.

- Ledger Entries and Balances – running totals for each account.

- Sub-Ledgers and Control Accounts – detail accounts (e.g. individual loans) that roll up to the GL.

Double-Entry Example

| Date | Account | Debit (Dr) | Credit (Cr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1 | Cash (Asset) | $75,000 | |

| Equipment (Asset) | $75,000 | ||

| Purchase of equipment for cash | |||

| Jan 8 | Inventory (Asset) | $25,000 | |

| Accounts Payable (Liability) | $25,000 | ||

| Bought inventory on credit | |||

| Jan 21 | Cash (Asset) | $15,000 | |

| Notes Payable (Liability) | $15,000 | ||

| Took out a loan (cash in, creating a liability) | |||

| Totals | $115,000 | $115,000 |

Table 1: Example journal entries posted to the general ledger, demonstrating double-entry balancing (debits = credits).

Real-World Use of Ledgers in Banks and PSPs

- Bank deposits: A customer deposits $1,000 → Cash (Asset) debited $1,000; Customer Deposits (Liability) credited $1,000.

- Loan repayment: A customer repays $500 → Cash (Asset) debited $500; Loan Receivable credited $500.

- PSP transaction: A buyer pays $100 via PSP → Merchant Account credited $100 (less fees); PSP records obligation to settle.

- Wallet top-up: A client adds $200 → Cash debited $200; Customer Wallets (Liability) credited $200.

- P2P transfer: User A sends User B $25 → Wallet A debited $25; Wallet B credited $25.

- Fee capture: A $2 fee → Wallet A debited $27; Wallet B credited $25; Fee Revenue credited $2.

In each of these examples, the common theme is that the ledger provides a unified, accurate record of money flow, which multiple teams (finance, operations, compliance) rely on. The GL is often connected to various systems: core banking, card processing, payment gateways, etc., feeding it transactions automatically.

When something goes wrong – say a batch of transactions doesn’t post – it’s quickly evident in ledger reports (balances out of line, or missing entries). Conversely, when everything works, the GL quietly ensures that millions of moving parts consolidate into balanced books at day’s end.

Notably, modern financial institutions strive to have these ledger updates in real time rather than waiting for end-of-day batches, because instant insight into balances and exposures is increasingly a necessity. We turn next to the evolution from traditional ledger systems to real-time accounting models.

Traditional General Ledgers vs. Real-Time Models

Historically, banks and businesses closed their books at the end of each day – meaning ledger updates for transactions were often processed in batch runs overnight. In such traditional general ledger systems, throughout the day you might see pending transactions, but the official ledger balances wouldn’t fully update until the batch posting and reconciliation occurred after hours. This approach made sense in an era of paper ledgers and early IT systems, but it introduced delays in knowing your true financial position. Errors or imbalances might only be discovered during nightly reconciliation, and fast reporting was difficult when data was only as current as the last batch.

Modern demands have given rise to real-time accounting models, where ledger entries are processed continuously as transactions occur. Many banks and fintechs are re-architecting their core systems (or adopting new platforms) to support real-time ledgers that update balances instantly and provide up-to-the-second accuracy.

According to SDK.finance, a leading core banking software provider, moving from batch-based accounting to real-time ledger systems “Is no longer optional. It is a prerequisite for financial institutions that want to compete in digital-first markets.”

Key Differences: Traditional vs Real-Time Ledgers

| Aspect | Traditional Ledger (Batch) | Real-Time Ledger |

|---|---|---|

| Processing method | Batch updates, often end-of-day | Continuous updates as transactions occur |

| Data accuracy | Delayed visibility; discrepancies only clear after reconciliation | Instant validation; balances always up-to-date |

| Transparency | Limited intra-day visibility into accounts | Full visibility at any moment for all accounts |

| Scalability | Strained by high volumes until batch can run | Designed for high-frequency digital transactions |

| Reconciliation | Performed post-factum (daily/weekly) – more manual intervention | Often continuous or automated reconciliation built-in to process |

| Operational risk | Higher risk of error accumulation before correction | Lower risk – errors detected and corrected sooner |

| Reporting & Decisions | Slower – financial reports and decisions made on yesterday’s data | Faster – real-time dashboards, proactive decisions possible |

| Customer experience | Delayed updates (e.g. a card payment might show next day) | Immediate reflection of transactions (balances update instantly) |

| Compliance support | Manual reconciliations and end-of-period adjustments needed | Automated audit trails, easier regulatory reporting |

Key Takeaways

-

The general ledger is the cornerstone of financial systems.

-

It structures accounts, journals, and balances under double-entry rules.

-

In banks and PSPs, it ensures deposits, loans, fees, and settlements are tracked accurately.

-

Reconciliation validates that ledger balances match external reality.

-

Real-time ledgers (like SDK.finance’s) are replacing traditional batch systems, enabling immediate accuracy, scalability, and built-in compliance.