Introduction: Why International Payment Infrastructure Is a Strategic Bottleneck

International payment infrastructure sits at the core of any business operating across borders. At early stages, payments often appear to be a straightforward operational function focused on:

-

accepting customer payments,

-

sending payouts,

-

maintaining basic reconciliation.

Within a single market, this setup is usually sufficient.

The situation changes as soon as a business expands internationally. Payment operations begin to span multiple countries, introducing additional complexity, including:

-

multiple currencies,

-

different clearing and settlement systems,

-

banks, EMIs, and other intermediaries,

-

regulatory requirements across jurisdictions.

What once looked like a simple payment setup quickly becomes a network of accounts, providers, and settlement flows that must operate in coordination.

This guide is intended for finance leaders, payment operations teams, and executives at global businesses scaling across multiple markets. Understanding international payment infrastructure is critical because it directly affects:

-

liquidity management,

-

reporting accuracy,

-

customer experience,

-

the ability to expand efficiently.

At this stage, international payments move beyond routine processing and become part of the business’s operational foundation. Without a well-structured infrastructure, they can limit growth rather than support it.

With this context, let’s define what international payment infrastructure means in practice and why it is more than just connecting payment rails.

What Is International Payment Infrastructure in Practice

Beyond Payments: Accounts, Ledgers, and Control Layers

International payment infrastructure is often misunderstood as simply having access to payment rails.

Payment rails are the networks or systems that enable the transfer of funds between parties, such as card processing, bank transfers, or local payment schemes. These are visible and tangible, making them easy to prioritize.

However, payment rails are only one layer of the system. Underneath them sit accounts, balances, and transaction records that determine who owns the money at any given moment and how it is accounted for. Without this layer, payments can be executed, but financial control remains fragile.

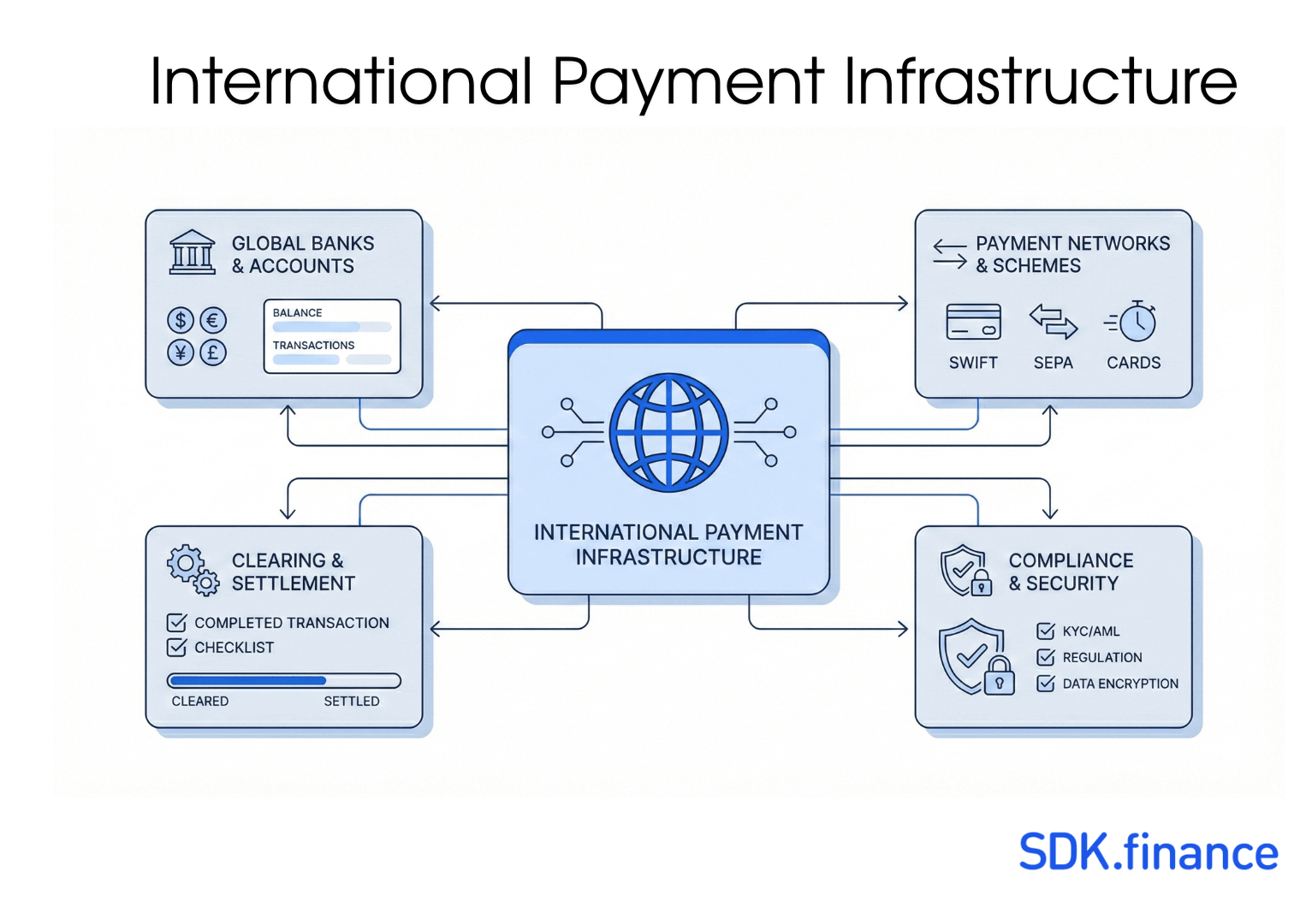

A complete infrastructure includes:

- Account structures (including bank accounts as the foundation for holding funds) that define where funds are held.

- A ledger – a system that records all movements and balances, enforces consistency, and preserves financial history.

- Operational logic that governs fees, limits, and transaction rules.

- Reporting and reconciliation mechanisms that provide financial visibility.

Ignoring these elements leads to situations where payments work, but the business cannot reliably explain its own financial position.

Summary: In essence, accounts define where money is held, ledgers track and reconcile all movements, and payment rails execute the actual transfers. Together, these layers form the backbone of international payment infrastructure, ensuring both operational efficiency and financial control.

The Difference Between Local and International Payment Setups

In a single-country setup, many complexities are hidden. Clearing cycles are predictable, currencies do not fluctuate, and reporting requirements are relatively uniform.

International operations remove this simplicity. Each country introduces its own settlement timelines, account structures, and operational constraints. The countries involved in a transaction can significantly affect processing times and requirements, as international transfers may be subject to varying regulations, banking practices, and cut-off times depending on the jurisdictions.

Funds may be held in different jurisdictions, processed by different institutions, and settled on different schedules.

Comparison Table: Local vs. International Payment Setups

| Aspect | Local Payment Setup | International Payment Setup |

|---|---|---|

| Currency | Single, stable | Multiple, fluctuating |

| Clearing Cycles | Predictable | Vary by country |

| Reporting | Uniform | Diverse, complex |

| Settlement Timelines | Standardized | Vary by jurisdiction |

| Regulatory Constraints | Minimal | Extensive, country-specific |

With these differences in mind, let’s explore the core building blocks that make up a robust international payment infrastructure.

Core Building Blocks of International Payment Infrastructure

Accounts and IBANs as an Infrastructure Layer

Accounts sit at the center of any international payment setup. They define where money is held and under which legal and operational framework. IBANs (International Bank Account Numbers) are often treated as a product feature, but in reality, they represent an infrastructure choice. Different models exist, including dedicated accounts, pooled accounts, and virtual account structures. Each model has implications for fund segregation, reporting granularity, and operational control.

In many international payment flows, a second bank – often referred to as bank b – is involved to facilitate the movement of funds between institutions, leveraging its relationships with intermediary or correspondent banks to ensure smooth cross-border transactions.

Choosing an account model without understanding its long-term impact can limit flexibility later, especially when transaction volumes increase or regulatory requirements tighten.

Once accounts and IBANs are established, the next layer involves the systems that move money—payment rails and clearing systems.

Payment Rails and Clearing Systems

Payment rails are the networks or systems that enable the transfer of funds between parties. Key types of payment rails used in international operations include:

- Wire transfers are a secure and direct method for transferring funds between banks across countries.

- Electronic transfers provide fast and secure digital fund movement.

- Card payments are widely used for cross-border transactions.

- Mobile payments offer a popular alternative for international transfers.

Cards, bank transfers, and local clearing systems each play a role in international operations.

However, payment rails do not define ownership or accounting logic. They execute instructions but do not provide a consolidated view of balances across providers and countries. Relying on rails alone forces businesses to reconstruct financial reality from external reports and delayed statements.

This approach becomes increasingly fragile as the number of providers grows.

To maintain control and visibility, businesses need a robust ledger and transaction accounting system.

Ledger and Transaction Accounting

A ledger is not simply a database of transactions. It is the system that defines balances, enforces consistency, and preserves financial history. In international payment infrastructure, each payment message serves as an instruction for the ledger to record and process the transfer of funds between accounts, often involving intermediary banks in cross-border transactions.

In international setups, a central ledger allows the business to maintain a single source of truth, even when money is processed through multiple external institutions. It enables real-time visibility, consistent fee application, and reliable reconciliation.

Without a ledger-driven approach, accounting becomes reactive and dependent on external data.

Summary: Accounts and IBANs define where funds are held, payment rails move the money, and the ledger ensures all transactions are accurately recorded and reconciled, providing a unified view of financial activity.

With the foundational layers in place, let’s examine the critical role of correspondent banking in enabling cross-border payments.

The Role of Correspondent Banking in International Payments

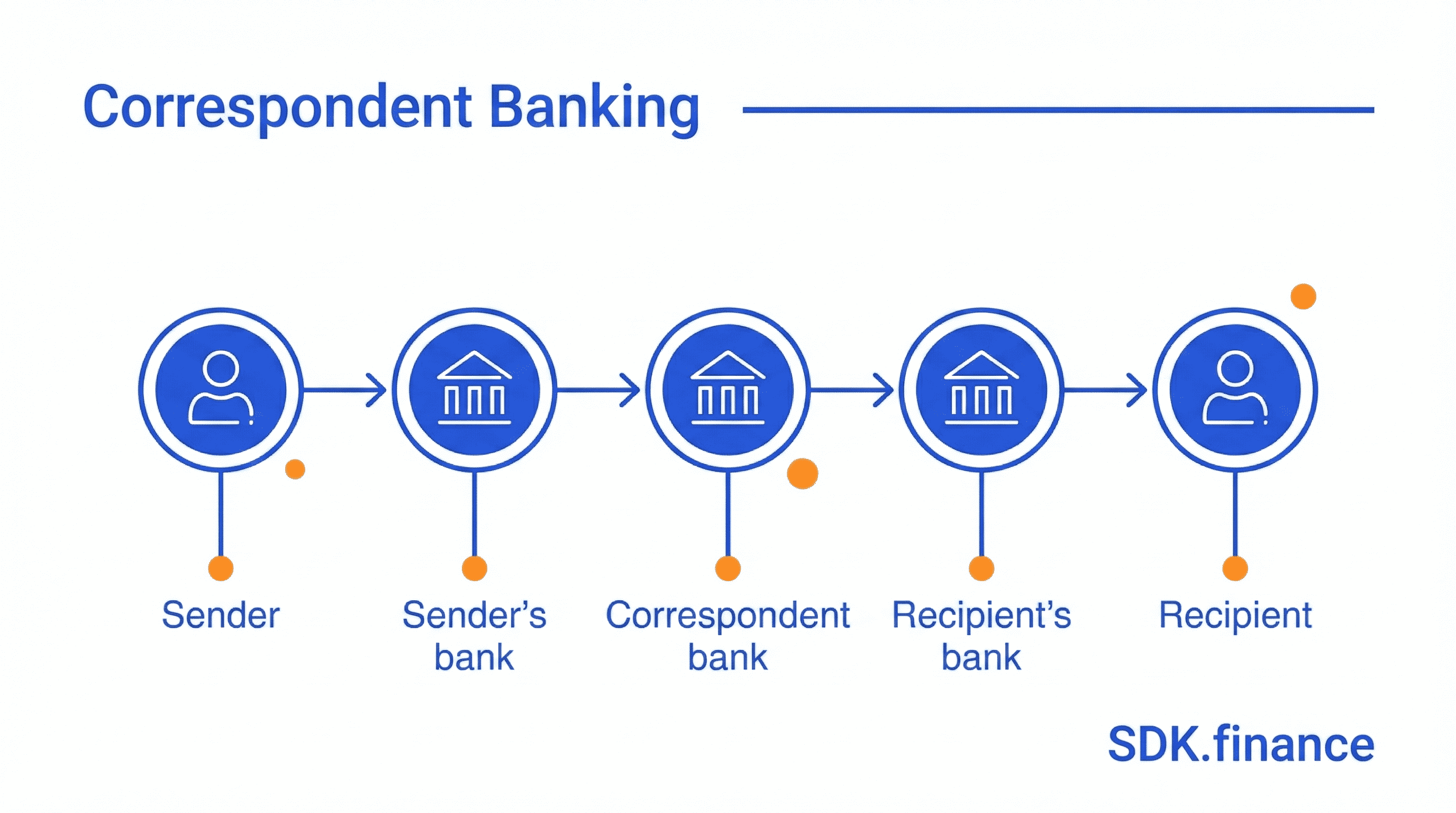

What Is Correspondent Banking?

Correspondent banking forms the backbone of cross-border payments, enabling financial institutions to process international transactions even when they lack a direct presence in the recipient’s country. In this model, banks establish relationships with other banks in different countries to facilitate the movement of funds.

How Correspondent Banking Works

The correspondent banking process typically involves the following steps:

- A customer initiates an international payment through their local bank (the respondent bank).

- The respondent bank sends the payment instruction to its correspondent bank, which has accounts in the destination country.

- The correspondent bank acts as an intermediary, transferring the funds to the recipient’s bank.

- The recipient’s bank credits the funds to the beneficiary’s account.

By maintaining accounts with banks in different countries, the correspondent bank can process cross-border transactions, settle international payments, and provide access to a wide range of cross-border payment services. This arrangement is especially critical for financial institutions that do not have branches or subsidiaries in every market where their clients do business.

Benefits of Correspondent Banking

The benefits of correspondent banking are far-reaching:

- Enables the smooth flow of international settlements.

- Supports global commerce and promotes financial inclusion by connecting domestic markets to the global economy.

- Facilitates trade, supplier payments, and global supply chain management for businesses.

- Provides individuals with services for international remittances and sending money to family members abroad.

Challenges Facing Correspondent Banking

However, correspondent banking relationships also present significant challenges:

- Managing transaction fees, navigating fluctuating exchange rates, and complying with complex regulatory requirements can increase the cost and complexity of cross-border payments.

- Maintaining relationships with multiple correspondent banks requires robust risk management and operational oversight, especially as each country may have its own rules and standards.

In recent years, the correspondent banking model has come under pressure. Heightened regulatory scrutiny, concerns over anti-money laundering (AML) compliance, and the rising costs of maintaining these relationships have led to a decline in correspondent banking networks, particularly in certain regions. This trend poses risks to financial stability, as it can limit access to cross-border payment services, increase transaction fees, and slow down international settlements—ultimately impacting the efficiency of global trade.

Industry Innovations and Future Trends

To enhance cross-border payments and address these challenges, the industry is turning to innovation. Technologies such as distributed ledger technology (blockchain) and real time gross settlement systems (RTGS, which are systems that transfer funds between banks in real time and on a gross basis) are being explored to streamline payment flows, reduce reliance on intermediaries, and make cross-border payments faster and more secure. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs, which are digital forms of central bank-issued money) also hold promise for simplifying international transactions and lowering costs.

International organizations, including the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), are actively working to set new standards and provide technical assistance to improve the efficiency and security of the global payment system. By fostering collaboration between central banks, financial institutions, and the private sector, these efforts aim to enhance cross-border payments, facilitate trade, and promote financial inclusion on a global scale.

With an understanding of correspondent banking, we can now examine why international payments and transaction fees become complex at scale.

Why International Payments and Transaction Fees Become Complex at Scale

Fragmentation Across Countries, Providers, and Financial Institutions

As businesses expand, they often add providers incrementally. A new market requires a new bank, a new payment institution, or a new clearing partner. The involvement of multiple payment providers—such as fintech companies, money transfer agents, and other financial institutions—can further increase fragmentation and operational complexity, as each may leverage different interbank networks and third-party partnerships.

Over time, this creates a fragmented landscape where each provider operates under different rules. Fragmentation increases operational overhead, as teams spend more time aligning reports, resolving discrepancies, and managing provider-specific exceptions. What initially seemed like a flexible setup turns into a rigid structure that is difficult to change.

Operational Risk and Loss of Visibility

Loss of visibility is one of the earliest warning signs of infrastructure stress. When balances are spread across multiple accounts and providers, understanding actual liquidity becomes difficult. Tracking and receiving cross-border payments adds another layer of complexity, as businesses must monitor incoming funds from various international sources and payment networks.

Delayed settlements, inconsistent reporting formats, and manual reconciliation processes increase operational risk. At scale, these issues affect not only finance teams but also decision-making at the executive level.

To avoid these pitfalls, it’s important to recognize common mistakes companies make when scaling international payments.

Common Mistakes Companies Make When Scaling International Payments

Treating Infrastructure as a Vendor Checklist

A frequent mistake is evaluating infrastructure based on feature lists. Questions such as “Does the provider support IBANs?” or “Can they process local transfers?” dominate decision-making.

These questions are necessary, but not sufficient. They focus on capabilities without addressing control, ownership, and long-term flexibility. Relying solely on corresponding banks for cross-border payments can introduce delays, higher costs, and limited transparency, making it risky to overlook the broader design of your international payment infrastructure. As a result, businesses assemble solutions that work individually but do not form a coherent system.

Optimising for Launch Speed Over Long-Term Control

Speed to market is important, especially in competitive environments. However, prioritising launch speed over structural soundness often leads to costly rebuilds later.

Investing in a robust international payment infrastructure from the outset can result in lower costs over time, as efficient, well-designed systems reduce transaction expenses and minimize the need for future overhauls.

Short-term solutions may hide limitations that only surface at scale. Replacing account models, migrating balances, or re-architecting transaction logic becomes significantly harder once the business is live across multiple markets.

To make informed decisions, C-level leaders should ask strategic questions before choosing providers.

Strategic Questions C-Level Should Ask Before Choosing Providers

Who Controls the Ledger and Transaction Logic

Control over the ledger determines who defines balances, applies fees, and enforces transaction rules. If this control sits entirely with external providers, the business becomes dependent on their reporting and timelines.

Understanding where transaction logic lives is essential for auditability and financial governance.

How Easily Can Providers Be Replaced or Added

Provider dependency is often underestimated. Accounts, balances, and historical data create natural lock-in. Designing infrastructure that allows providers to be replaced or added without rewriting core logic reduces long-term risk.

What Happens When the Business Scales Internationally

Scaling internationally is not just about adding countries. It multiplies operational complexity. Efficient international money transfers become critical for businesses looking to scale payment operations across borders, as they ensure smooth and reliable cross-border transactions. Infrastructure should support centralised oversight while accommodating local requirements.

Without this balance, growth leads to fragmentation rather than efficiency.

Viewing payment infrastructure as a long-term business asset is essential for sustainable growth.

Infrastructure as a Long-Term Business Asset

Why Payment Infrastructure Is Not a One-Off Project

Payment infrastructure evolves alongside the business. Regulatory changes, new markets, and increased transaction volumes require ongoing adaptation.

Treating infrastructure as a one-off implementation ignores this reality and leads to accumulated technical and operational debt.

Designing for Evolution Instead of Rebuilds

Designing for evolution means separating core accounting logic from external providers and payment rails. It allows the business to adapt incrementally rather than through disruptive rebuilds.

This approach reduces risk and supports sustainable growth.

How Businesses Evaluate Vendors for Global Payment Capabilities

When businesses evaluate vendors for global payment capabilities, the focus goes beyond geographic or currency coverage. While these factors are important, experienced organisations assess how payments are executed at the infrastructure level. Many providers rely on intermediary networks or correspondent relationships, which can introduce delays, additional costs, and limited transparency as transaction volumes grow.

In practice, vendor evaluation often centres on a small set of structural considerations:

-

how accounts and IBANs are structured and managed,

-

the level of visibility into transaction flows and balances,

-

settlement speed and access to funds across regions,

-

reliance on direct access to local payment rails versus third-party intermediaries.

These factors determine how well a payment setup supports reconciliation, liquidity management, and regulatory alignment across markets.

Ultimately, selecting a global payment vendor is treated as an architectural decision rather than a procurement exercise. Businesses that evaluate vendors based on infrastructure depth and control are better positioned to scale internationally without frequent re-architecting, while solutions chosen primarily for speed or surface-level coverage often become constraints as operational complexity increases.

Let’s look at a practical example of how to build a scalable cross-border payment infrastructure.

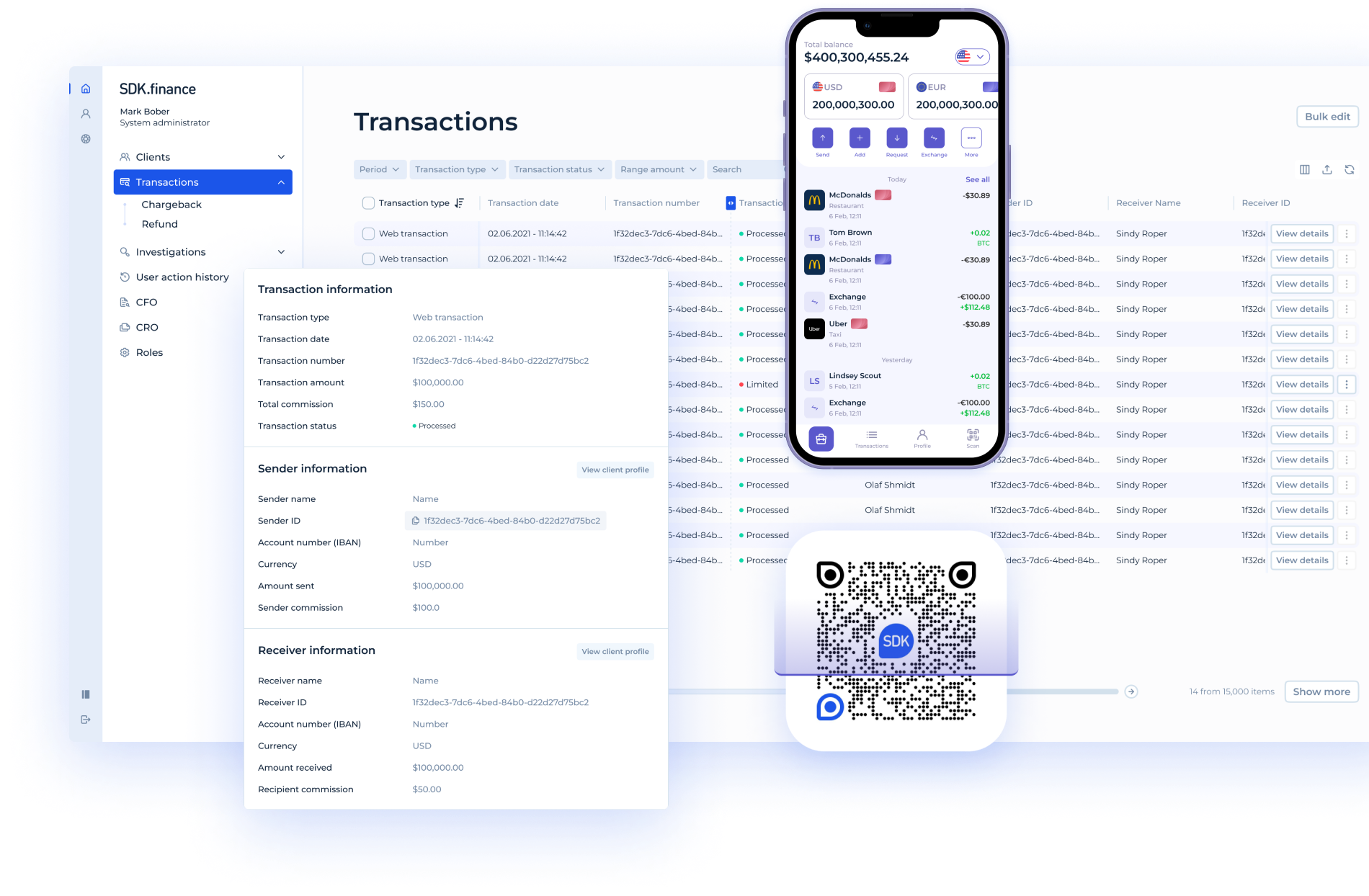

Best Payment Infrastructure Architecture for Global Scale: How SDK.finance Approaches Payment Infrastructure

SDK.finance’s Ledger-Centric Architecture

Designing international payment infrastructure requires more than connecting payment rails or opening accounts in multiple countries. It requires a system that keeps financial logic, transaction control, and operational visibility under the business’s control, even as providers and geographies change.

SDK.finance approaches cross-border payments as an infrastructure challenge, not a collection of integrations. The Platform is built around a ledger-centric architecture that separates core accounting and transaction logic from external payment providers, banks, and clearing systems.

Benefits for Global Businesses

This approach allows businesses to:

- Maintain a single source of truth for balances and transactions across countries and currencies.

- Integrate multiple banks, EMIs (Electronic Money Institutions, which are licensed entities that issue electronic money and provide payment services), and payment providers without duplicating business logic.

- Replace or add providers as the business scales, without rebuilding the core system.

- Retain operational and financial visibility as transaction volumes and jurisdictions grow.

Key Features of the Platform

SDK.finance’s payment infrastructure is designed to support complex cross-border scenarios, including:

- Multi-currency accounts

- International transfers

- Settlement orchestration

- Reconciliation across multiple providers

By combining a transaction ledger, extensive APIs, and operational backoffice tools, the Platform enables companies to structure international payments in a way that supports long-term growth rather than short-term launches.

For organisations building or scaling cross-border payment operations, this architectural approach provides a stable foundation that balances flexibility, control, and operational clarity.

To wrap up, let’s summarize the key takeaways and address common questions about international payment infrastructure.

Conclusion: Building Payments That Support Growth, Not Limit It

International payment infrastructure is a strategic foundation, not a peripheral system. Decisions made at the early stages shape operational control, financial visibility, and scalability for years to come.

Businesses that approach payments as an integrated infrastructure, rather than a collection of vendors, gain flexibility and resilience. They are better positioned to expand internationally without compromising control or efficiency.

Understanding the architecture comes before choosing providers. This perspective sets the groundwork for international growth that is structured, predictable, and sustainable.